UNDIP, Tolitoli, Sulawesi Tengah (October 1, 2025) – Behind the slogan of Indonesia as an agrarian nation lies an unfinished irony. The backbone of food sovereignty, especially in transmigration areas, continues to face multidimensional challenges: limited infrastructure, restricted market access, and unresolved land ownership issues.

The Basidondo Transmigration Area in Tolitoli Regency, Sulawesi Tengah, holds vast potential for cocoa, coconut, and coffee production. Yet without proper technology and transport access, this potential often fades into missed opportunities. Muliasari Village, one of the transmigration settlements in Lampasio District, stands as a stark example of this development paradox.

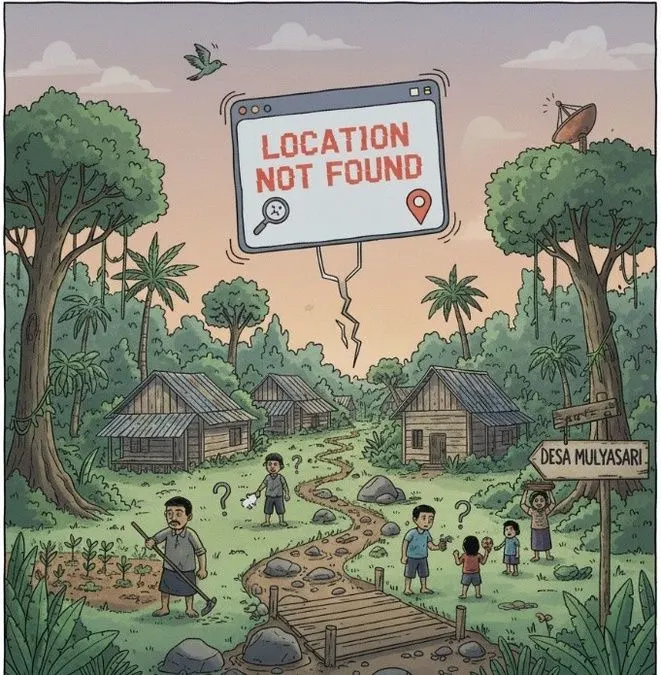

A Village Missing from the Map

Muliasari is more than remote; it has nearly disappeared from digital maps. Its name and location are difficult to find on navigation apps, as if its existence only lives in the memories of its residents. Weak telecommunication signals further symbolize the village’s disconnection from integrated development programs.

Decades ago, transmigrants came with hopes of a better future. Today, many are trapped in isolation. Their crops are abundant, but broken roads and high transport costs make it difficult to sell their harvest. They persist as resilient farmers, though markets rarely work in their favor.

The Snare of Land Status

Muliasari’s biggest challenge is the lack of clarity in land ownership maps. Land that should rightfully belong to transmigrants is often overlapped with protected forest areas or entangled in disputes. This phenomenon has left farmers exhausted and waiting for certainty.

Still, the villagers resist quietly. They clear land communally, plant together, and share the yields in a spirit of kinship. This self-help effort serves as a silent protest against bureaucratic uncertainty—showing that farmers will always find ways to sustain both themselves and their land.

Voices from the Field

These concerns were documented during the visit of the UNDIP Patriot Expedition Team (TEP), consisting of Septrial Arafat, Risa Nurhaliza, Nok Ayu Nurasih, Emanuel Clasius, and Zaenal Abidin. The team went directly to Muliasari to map its potential and listen to residents’ grievances.

“We are just ordinary people. Our only hope is the government. If the government doesn’t care, where else can we turn?” said one farmer in sorrow. “We only ask for clarity in land ownership maps. With certainty, we can farm in peace and turn our harvest into blessings, not just sweat,” he added.

According to the team, land issues and poor infrastructure are two critical challenges that must be urgently communicated to the Ministry of Transmigration. The expedition demonstrated that mapping transmigration potential is not only crucial for understanding real community conditions but can also serve as a foundation for national programs to build new centers of economic growth.

This collaborative effort embodies the spirit of “Noble and Valuable UNDIP,” aligning with the vision of “Diktisaintek Berdampak,” where research and community engagement directly respond to people’s needs. More broadly, the work in Muliasari contributes to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

- SDG 1 – No Poverty, through expanding economic access for transmigrant farmers.

- SDG 2 – Zero Hunger, by strengthening food security based on local commodities.

- SDG 9 – Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure, by promoting transport development and technology adoption.

- SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities, by improving livability in transmigration areas.

- SDG 17 – Partnerships for the Goals, through collaboration among communities, government, and universities.

A Dead-End Road to the Market

The dirt road linking Muliasari to economic hubs has long been in disrepair. An old bridge from the primary agricultural production zone is nearly unusable, especially during the rainy season. As a result, transport costs skyrocket, and crops—particularly cocoa—must be sold at a low price to local middlemen.

For residents, this infrastructure gap is a “dead-end road” to prosperity. Without proper access, reaching broader markets remains impossible.

Hopes Hanging in the Balance

This situation leaves Muliasari at a crossroads: endure the hardship with limited means or slowly sink into obscurity. What residents need is not only physical infrastructure but also settlement of land disputes, legalization of ownership maps, and reliable bridges to markets.

Muliasari, a village nearly erased from digital maps, is now demanding its place on the national development map. Only then can the sweat of transmigrant farmers truly yield prosperity—not just stories of abandoned hope. (Public Communication/ UNDIP/ Patriot Expedition Team Tolitoli, ed. As)